You can't spend two years in SE Asia without encountering something of the wild side. We're not extreme adventurers; we are basically homebodies who like to travel with our kids. But here in SE Asia, we've come into contact with some pretty amazing critters, so I'm looking back on our time here and reminiscing a little about how easy it is to get close to nature here in Asia.

SNAKES ON A BOAT!We begin with our newest passenger -- an uninvited guest who somehow stowed away in Phuket, Thailand, and hitched a ride to Langkawi, Malaysia. By all accounts he appears to be a

pit viper -- based o his behavior and coloring/ markings. Not the kind of guest you want onboard. Because of him, we got in touch with a couple snake experts, first in Thailand but as we were sailing south they were out of reach and unable to help first-hand (though they did hold our hands metaphorically, and we were grateful for that), then with a local snake expert in Langkawi.

![]() |

| Othman clarifying a few things about snakes. |

Othman Ayeb came to

Momo for an afternoon last week and talked all about his own experiences with snakes plus the likelihood of whether our stowaway was still with us -- and also how to care for a bite in case we were to startle Mr Viper and get one. We are now armed with tobacco and vinegar and also know how to use a sharp razor to bleed a bite in case it comes to that. We understand the different kinds of anti-venoms but also that they won't really help when we are offshore. But we are not nearly as fretful as we were upon first seeing the snake fall out of our mainsail and onto the deck. Something about Othman's calm manner helped us feel more at ease with the idea of this stowaway. Lola even resumed sleeping in the forepeak (we had assumed he could be up there since our last sighting saw him come down the rig and slither forward, up under the dinghy on the foredeck).

We were all smiles by the time Othman left

Momo that afternoon.

We then went to his house for a visit with his family and his pet King Cobras. All quite fascinating -- and we'll write more about that later. But for now, here are some photos of Othman and some of his pets (the common cobra and the king cobra). He's a man of great energy and passion and shared many stories about the wildlife of Langkawi.

![]() |

| Othman's King Cobra -- 3.5 meters in length. We watched a video of this snake eating a monitor lizard. |

![]() |

| Othman demonstrating the common cobra's warning response. |

![]() |

| Showing a little love -- the common cobra enjoys this kind of stroking on the back of his head. |

![]() |

| Othman is at ease with the cobra as he talks to us for a long while with the cobra right at his fingertips. |

![]() |

| Showing the 'warning' reflex of the cobra -- unlike the viper, who will strike with no warning. |

![]() |

Some reading materials Othman shared -- including his page in the 1999 Guiness Book of World Records. We had seen one of these gliders in Thailnad but did not capture it on camera.

|

![]() |

| Python in the Langkawi Wildlife Park -- this fellow is 7 meters and was first seen by Othman some six years back. He helped release him into a wild area where he'd be farther away from populations, but he encountered him once more when he received a call from a friend whose dog was being eaten by a very large python. Othman arrived on the scene to help capture the snake and discovered it was in fact the very same one from many years back. "is that you, my old friend," he recalled saying to creature. So he helped contain it and get it to the facility where it could live out its years in a place where it's no threat to any other creatures -- except the road kill that it feasts on each month. |

|

*

KOMODO DRAGONS AT CHRISTMASSnakes are new to us, but we've seen plenty of monitor lizards since we've been in SE Asia: they amble across roads, they sit lazily in fields, they climb trees. One even slithered near us at a resort pool and climbed in, swam to the other side and proceeded to carry on his way down toward the beach! But besides monitor lizards, we also had the immense pleasure of seeing the mighty Komodo Dragon -- something we've been curious about ever since we first encountered

Last Chance to See. And something entirely different from the more docile monitor lizard. We spent Christmas Eve 2013 with these creatures on Rinca Island, Komodo National Park, Indonesia. With them and a guide, that is.

![]() |

| Komodo dragon, Rinca Island, Indonesia |

![]() |

| Water buffalo heads -- the only thing komodo dragons don't eat, as they can't digest the skulls So the rangers nail them up around the park -- effectively sobering decor. |

![]() |

| Pretty big guy ambling by... |

![]() |

| You don't really hear them as they quietly breathe in and sense their surroundings. |

![]() |

| Komodos lounging near the ranger station. Benie and the kids with our guide Arif near the ranger station on Rinca Island. The dragons look slow and relaxed, yes -- but they can take off at remarkable speeds. They feast on water buffalo and are known to attack humans. We didn't go any nearer than this -- and only here at the ranger station. |

![]() |

| They look laze and slow -- but that's deceptive. One of them has been spray painted on his back (not pictured here) so the guards know him and keep a greater distance; he is the one who has attacked people. When we visited, our guide told of various people who had been killed in recent years: a Swiss tourist and a local child from a nearby village. |

![]() |

| Our guide Arif sharing stories -- and always with his long stick. |

*

BIRDS, BEAUTIFUL BIRDSMore colorful than the Komodos are the many birds of SE Asia. Too many to count and name but all enchanting. We encountered birds in Bali, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. Everywhere we went, really. I spent a day in Kuala Lumpur's Bird Park with Jana, plus other bird parks around the area: you can't go very far without encountering a park for local and exotic bird species. We also visited the Wildlife Park in Langkawi, where they have a great many creatures large and small -- including the 7-meter python pictured above, who was rescued and cared for by our friend Othman.

![]() |

| Close-up in Bali. |

Birds are part of the everyday fabric of life in this part of the world: they hang prettily in their cared-for cages in shops, in restaurants, in homes.

![]() |

| Pet in the petrol shop in Ambon, Indonesia. |

You're not exactly in the 'wild' in the bird parks,but they do let you get up close and personal -- and they are usually trying to educate you about bird behavior, habitat and survival.

The hornbills are spectacular. We took a video of the call of one once -- amazing throaty sound. They tend to swoop in at the end of the day; you can see them all over Langkawi. You

hear them before you see them, a great whomp-whomp of the wings. We met a local man who told us to watch for them in the evenings -- to sit quietly and look in the trees at the water's edge, or in the lower sections of Gunung Raya, Langkawi's highest peak. Sure enough, that very evening we saw (and heard) hornbills -- and then grew accustomed to seeing them in the trees.

But we like the smaller birds, too.

![]() |

| Budgies! We love budgies! |

![]() |

| In Kuala Lumpur |

![]() |

| Many peacocks strutting around the KL Bird Park. |

![]() |

| Langkawi Wildlife Park |

*

NON-VENOMOUS VISITORS ON MOMOSometimes birds come visit

Momo, too.

![]() |

| At anchor in Komodo National Park, Indonesia. |

![]() |

| Crow takes flight -- in Komodo National Park. |

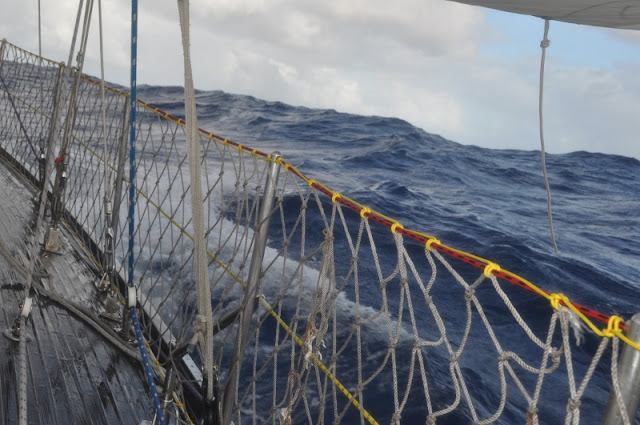

Sometimes we get other hitchhikers.

And once we had a wee swallow arrive on

Momo, en route from Bali to Malaysia. First, he hitched a ride on Jerome, our windvane.

![]() |

| Then he moved to the netting. |

![]() |

| And stayed here for some time... |

![]() |

| Lola and Jana tried to entice him to eat, since he stayed with us so long. |

![]() |

| ...but he was not very hungry... |

![]() |

| ...and he flew from one place to the other... |

![]() |

| ...landed on Bernie's hand... |

![]() |

| and visited with Jana. |

That little sparrow died in the night on our back deck. I kept watch over him while he slowed and then breathed rapidly, his tiny chest beating fast, before expiring. Jana said her goodbyes in the morning.

*

GIANTS AND ANTSNot all our encounters are with animals. One of the wildest encounters we had was with tree.

Actually, the close encounter was Bernie's, in Singapore. Seems he got a little too close despite the warning. And next thing we knew, his elbow, which was punctured by one of these spines, ballooned with alarming liquidy content.

Other tree adventures included mighty roots in great forests, nutmeg and almond plantations of the Spice Islands, the Botanic Garden of Penang, Malaysia and the tropical forest of the Salt Crater Lake on

Pulau Satonda, Indonesia.

![]() |

| Ants and beautiful flowers in the Botanic Gardens, Penang, Malaysia. |

![]() |

| Great Salt Crater, Pulau Satonda, Indonesia |

![]() |

| More ants -- Pulau Satonda, Indonesia |

![]() |

| Seaweed offering from the salt lake in Satonda. |

![]() |

| We never tire of the peaceful lilyponds all over SE Asia, too. This one in Singapore. |

![]() |

| Tree in Tioman Island, Malaysia |

![]() |

| Bamboo forest, Langkawi, Malaysia -- there's something about this wild and fast-growing stuff that I really love. |

*

CHEEKY MONKEYS!Then there are the other primates: the common macaque monkeys, the proboscis monkeys, the endangered orangutans and gibbons. We can't help but be fascinated by them -- on the side of the road in Langkawi, in Bali's Monkey Forest, in Thailand's

Gibbon Rehabilitation Project, in Malaysia's

Orangutan Island.

We saw monkeys in many places but the first time we really got close to them was in Bali's Monkey Forest. Still, you have to be careful; they'll steal your glasses or food, if you have any in your pockets. They are accustomed to humans, so they aren't shy. The babies are most curious and adorable. The big ones will climb on you just as quickly, though. You learn not to make eye contact and a few other ways to be respectful. In most places we did not just stroll up and handle monkeys -- not advisable. But in the Monkey Forest there are guides posted around to monitor monkey (and human) behaviors. |

![]() |

| Slightly blurry but I just loved this little family. |

![]() |

| Lunch time! |

![]() |

| Typical shoreside monkeys -- in Rinca, Indonesia. |

![]() |

| Camouflaged! |

![]() |

| Little chocolate monkey in the trees, Penang Botanical Garden. |

![]() |

| They can scurry up light poles just as fast as they do up tree trunks. |

![]() |

| in Penang Botanical Gardens |

![]() |

| in Penang Botanical Gardens |

![]() |

| Cheeky monkey!! |

![]() |

| Shy guy in the tree -- Langkawi, Dayang Bunting, Lake of the Pregnant Maiden |

![]() |

| You have to look close but there were lots of these fellows frolicking in these trees. Langkawi. |

![]() |

| Langkawi -- Lake of the Pregnant Maiden. These guys are not shy and you have to walk down this walkway past all of them to get to the swim area at the end of the lake. |

![]() |

| Uluwatu Temple, Bali -- temple monkey |

ENDANGERED PRIMATES: GIBBONS AND ORANGUTANSOne of the last things we did in Phuket before leaving last month was visit the

Gibbon Rehabilitation Project-- GRP, which for us has always stood for fiberglass but now holds more meaning.

The project was started in 1992. At that time they were almost completely wiped out -- extinct! -- due to poaching. The project collects injured animals from the wild, saves them from abusive owners and monitors the populations, ensuring families are released together for better chances of survival. The population is now making a comeback.

Why do gibbons suffer still? There is a huge tourism trade for photos with gibbons -- the cute, fuzzy baby ones. The babies are collected from their parents and used -- photo with a baby gibbon? -- and then, as they grow older, they are set aside or even worse outright physically and emotionally abused. We heard from our guide of several cases of gibbons that they've taken in who are recovering from beatings -- and we saw one who had lost one hand and one foot from abuse by her owner. She will not be released into the wild but cared for here for the rest of her life. The main goal, however, is to nurture families and set them free.

From the GRP page: Don't have your photograph taken with a gibbon or use the bars they are kept in. Report poaching to the National Park Headquarters or the Natural Resources and Environment Crime Suppression Division or the Department of National Parks: Wildlife and Plants.

The GRP Facebook page is

here. Go on, Like it!

![]() |

| These two are always together -- friends for life and inseparable. |

Earlier in the year, we visited Malaysia's

Orangutan Island, a similarly organized facility where orangutans are protected, nurtured and rehabilitated, with the goal being to release them back into the jungles of Borneo. Orangutan Island is larger than the gibbon sanctuary -- a whole island in the middle of an strangely defunct-feeling Disney-like theme park (very odd) -- but these creatures need room to move. The thing about this facility that really struck us was the way

the visitors are the ones enclosed, not the wild animals. We walked through portions of the island (only a small portion is open to viewers) and we were the ones caged: an enclosure around us on both sides and up over our heads kept us a considerable distance from the orangutans, while they were free to roam about in their natural habitat. Hence, my caged photos with blocked views. But I really like how the only way to view these creatures is through this distance; even the guides only ever enter the territory if an orangutan is sick or in need of routine medical care.

![]() |

| BFFs |

![]() |

| She is lovely. |

![]() |

| Big Daddy! |

![]() |

| Walking through with our guide. You can see how the enclosure works, keeping us in. |

![]() |

| The humans' enclosure goes up overhead, too, so you can see the animals in the trees. |

![]() |

| Young one on the move. |

![]() |

| Stopping to say hello. |

Orangutan Island also has a medical facility, of course. Some of the animals need serious care when they are rescued (babies without parents, for example), and some need continuing care as they grow and change. There are educational brochures and plenty of places to inform yourself further.

When we were there, two young ones were in the hospital facility for blood tests. They were wild and woolly and interacted with us quite a lot through their windowed enclosure. One made a game of passing a leafy branch back and forth over the top -- where it was barred and open -- to a girl who was also there visiting with her family. It was quite something to see the way this animal played with her; there was a sense of play and insisting on 'my turn, your turn' that was fascinating to watch.

![]() |

| Small girl and orangutan -- equally curious about the other. |

![]() |

| Jana making contact. |

![]() |

| Jana could connect her hand here through the glass to the hand/ foot of the animal. |

You can read about the care program and the facilities at the island, as well as their release program,

here. The challenge is making sure the animals are ready for release (they use an interim pre-release island to observe and carry out the release in stages) and ensuring there is suitable forest for the orangutans to enter or re-enter. More about the release process is

here; and video of a release can be viewed

here.

*

CIVETS AND COFFEE: TO BLING OR NOT TO BLINGAnother case of humans interacting with the wild...

In Bali, we were introduced to the famous

cat-poo coffee, more formally known as

Kopi Luwak and made from the beans of coffee beans ingested by civet cats and then expelled, cleaned, roasted and ground. Said to be the 'blingest' coffee in the world, this coffee is, yes, expensive. We paid $5 for a small cup, and did not dare purchase any more. The taste was smooth, yeah, and I admit to being intrigued by the whole idea.

![]() |

| Michelle's mother sniffing the civet coffee beans |

But you spend enough time in these parts, you start to see past the initial intrigue. Trauma and drama hide behind this tourism 'seller' which brings people by the busload to small coffee 'plantations' and even sees a lucrative export trade. Kopi Luwak was first exported to western countries by

Toni Wild in 1991. But Tony has since recanted his devotion to this coffee and

speaks out passionately about the practices of keeping the wild civet cat in captivity for coffee production and export. In the last couple years, he's launched a worldwide campaign to stop what calls a

'cruel, fraudulent trade'. He's now looking for a way to produce sustainable coffee. His Facebook campaign --

Kopi Luwak: Cut the Crap -- can be found

here.

*

WILD THINGS UNDERSEA

Finally, it's not possible to talk about SE Asia without looking under the surface. We are always mesmerized underwater -- by corals, fishies, dolphins and sea turtles, Jana wrote up a school report about the turtle sanctuary of Tioman Island, where we had a tour of their rescue and egg care facility, and we swam one afternoon in the waters of Redang Island with these graceful creatures. Like with dolphin or whale, I never get tired of this kind of thing. We first swam with turtles and dolphins in Hawaii in 2005, and I'm never any less enchanted when I get in the water with one of these amazing beings -- who are also surprisingly quick in the water.

![]() |

| Tioman Island, Malaysia, Turtle Sanctuary |

![]() |

| Getting an introduction to the Tioman turtles |

![]() |

| Jana at Tioman Island |

![]() |

| Meeting Jo, the blind turtle who is cared for at Tioman |

![]() |

| Protecting turtle eggs at Tioman |

![]() |

| Creeping along the bottom at Redang Island |

![]() |

| My Wild Thing - Jana, in Redang Island, Malaysia |

![]() |

| Christmas Tree Worms in Koh Tao, Gulf of Thailand |

![]() |

| Christmas Tree Worms -- Spriobranchus giganteus |

![]() |

| Corals in the Gulf of Thailand |

![]() |

| Michelle and Jana in Redang |

WILD LUMINSCENCELastly, a brief mention of the oddest wild encounter of all: the case of

bioluminescence we experienced in the Gulf of Thailand one night in 2014 -- mystical and strange and impossible to describe. A pulsing thing that lasted hours and was unlike any other bioluminescence we'd ever seen -- fish zigzagging through the water or the dinghy creating a glowing bow wake, for example. Turns out, it was a rare experience and we were luckier than a scientist who's been tracking this phenomenon his whole life, trying to get a glimpse. We wrote it up in a blog entry

here.